Geneviève Fieux-Castagnet and Gerald Santucci

September 2019

INTRODUCTION

The phrase “Artificial Intelligence” is not new. The Dartmouth Conference of 1956 was the moment when Artificial Intelligence gained its name, its mission, and its first bunch of famed scientific leaders – Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon, Nathan Rochester.

The concept, however, goes far back in antiquity, with myths, legends, stories of artificial beings endowed with “intelligence” or “consciousness” by master craftsmen, and in history, with the building of realistic humanoid automatons by craftsmen from every civilization, from Greece and Egypt to China, India and Europe, and later of calculating machines by many mathematicians like Gottfried Leibniz, Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace, and so forth.

Then, developments accelerated in the second half of the twentieth century, with a sequence of periods which scholars called “the golden years” (1956-1974), “the first AI winter” (1974-1980), “Boom” (1980-1987), and “Bust: the second AI winter” (1987-1993). After 1993, due to increasing computer power, the field of Artificial Intelligence finally achieved some of its oldest goals by being applied and used successfully throughout the industry, although hardly visible for non-specialists.

Since 2000, access to large amounts of data (“big data”) collected from billions of “Internet of Things” smart connected devices, faster computers, and new machine learning techniques were successfully applied to many problems throughout the economy. Advances in ‘deep learning”, in particular deep convolutional neural networks and recurrent neural networks, drove progress and further research in image and video processing, text analysis, and speech recognition.

Today we begin to live with a new customised dictionary or lexicon containing words like “algorithm”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, or “neural network”, which are an integral part of our cultural landscape.

At the same time, we see almost all countries of the world launching comprehensive research and development programmes geared to enhance Artificial Intelligence skills and to leverage this discipline for economic, sustainable and inclusive growth as well as social development. Decision-makers are aware that Artificial Intelligence, as an unprecedented revolutionary, disruptive and once-in-a-generation phenomenon, presents a tremendous potential that shouldn’t be ignored, and in fact must be unleashed. Beyond the short-term financial impact of Artificial Intelligence deployment, nation-states are striving to hit far greater achievements in domains like healthcare, agriculture, education, smart cities, mobility and transportation, and so on.

Artificial Intelligence is poised to disrupt our world. With intelligent machines enabling high-level cognitive processes like thinking, perceiving, learning, problem solving and decision making, coupled with advances in data collection and aggregation, analytics and computer processing power, it presents opportunities to complement and supplement human intelligence and enrich the way people live and work.

Every new day brings evidence of the formidable opportunities created by Artificial Intelligence, but also the immense societal and ethical, and even civilizational challenges that it poses to humanity. At the same time countries are seeking to boost R&D in Artificial Intelligence, they design and debate their own legislative and regulatory approaches aimed at addressing these challenges. International organisations such as OECD and the European Commission are also working on “guidelines” about ethics in Artificial Intelligence and associated technologies.

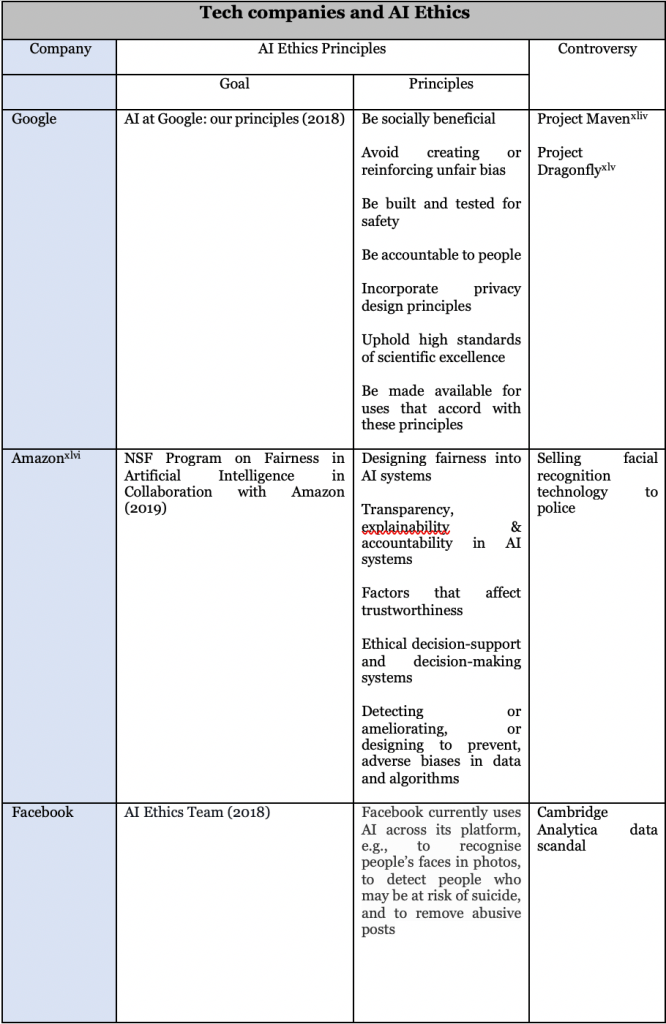

In the past few years, tech companies – notably the “GAFA” in the United States (Google, Apple, Facebook Amazon) and the “BATX” in China (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, Xiaomi) – certainly seem to have embraced ethical self-scrutiny: establishing ethics boards, writing ethics charters, and sponsoring research in topics like algorithmic bias.

It is too early to say if these boards and charters are changing how these big companies work or holding them accountable in any meaningful way. But what matters is that both public sectors and private companies are working, sometimes separately but more and more often collaboratively, in order to strike a balance between innovation and protection, business and ethics.

We think time is ripe to provide a framework conducive to a better understanding and structuring of the main recent developments, opportunities and problems.

This is the purpose of this essay.

Artificial Intelligence : a global challenge of disruptive change

“Fifty thousand years ago with the rise of Homo sapiens sapiens.

Ten thousand years ago with the invention of civilization.

Five hundred years ago with the invention of the printing press.

Fifty years ago with the invention of the computer.

In less than thirty years, it will end.”

Jaan Tallinn, Staring into the Singularity, 2007

The phrase “Artificial Intelligence” – in short AI – conjures concepts like robotics, facial recognition, chatbots, or autonomous vehicles. But in fact, well before the advent of even electricity, humans were fixated on creating artificial creatures, for example medieval alchemists who believed they could transform things into forms of artificial life (“philosopher’s stone” or “elixir of life”), thus exploring immortality, or Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the late 16th century rabbi of Prague who invented the Golem out of clay, with the intention of protecting the Jewish people from attacks.

The age-old desire to expand intelligence was accelerated in the 1940s with the creation of the computer, providing scientists with the power to generate models capable of solving complex tasks, emulating functions previously only carried out by humans. The advent and maturation of artificial intelligence is now blurring the boundaries between human and technology. Where do we end, and where does technology begin?

The first neural network stemmed from the idea that rational thoughts could be transformed into formulaic rules. The first step towards artificial neural networks came in 1943 when Warren McCulloch, a neurophysiologist, and a young mathematician, Walter Pitts, wrote a paper on how neurons might work. They modelled a simple neural network with electrical circuits. The early timelines of Artificial Intelligence include genial inventors such as Alan Turing, Claude Shannon, or Ada Lovelace. From the work of the “Godfathers of AI”, Yoshua Bengio, Yann LeCun and Geoffrey Hinton, working away on convolutional neural networks during the “AI Winter” of the 1970s, emerged the 21st century ground-breaking work being done in research and industry applications to solve some of the world’s biggest challenges.

There is currently no agreed definition of “Artificial Intelligence” (…) AI is used as an umbrella term to refer generally to a set of sciences, theories and techniques dedicated to improving the ability of machines to do things requiring intelligence. An AI system is a machine-based system that makes recommendations, predictions or decisions for a given set of objectives. It does so by: (i) utilising machine and/or human-based inputs to perceive real and/or virtual environments; (ii) abstracting such perceptions into models manually or automatically; and (iii) deriving outcomes from these models, whether by human or automated means, in the form of recommendations, predictions or decisions.[1]

The two tables below give the main common terms used in Artificial Intelligence and some key milestones in the Artificial Intelligence Timeline.

Common terms used in Artificial Intelligence[2]

Algorithm

A finite suite of formal rules/commands, usually in the form of a mathematical logic, that allows for a result to be obtained from input elements. They form the basis for everything a computer can do, and are therefore a fundamental aspect of all AI systems.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

An umbrella term that is used to refer to a set of sciences, theories and techniques dedicated to improving the ability of machines to do things requiring intelligence.

AI system

A machine-based system that can make recommendations, predictions or decisions for a given set of objectives. It does so by utilising machine and/or human-based inputs to: (i) perceive real and/or virtual environments; (ii) abstract such perceptions into models manually or automatically; and (iii) use model interpretations to formulate options for outcomes.

AI system lifecycle

A set of phases concerning an AI system that involve: (i) planning and design, data collection and processing, and model building; (ii) verification and validation; (iii) deployment; (iv) operation and monitoring; and (v) end of life.

Automated decision-making

A process of making a decision by automated means. It usually involves the use of automated reasoning to aid or replace a decision-making process that would otherwise be performed by humans. It does not necessarily involve the use of AI but will generally involve the collection and processing of data.

Expert system

A computer system that mimics the decision-making ability of a human expert by following pre-programmed rules, such as ‘if this occurs, then do that’. These systems fuelled much of the earlier excitement surrounding AI in the 1980s, but have since become less fashionable, particularly with the rise of neural networks.

Machine learning

A field of AI made up of a set of techniques and algorithms that can be used to “train” a machine to automatically recognise patterns in a set of data. By recognising patterns in data, these machines can derive models that explain the data and/or predict future data. When provided with sufficient data, a machine learning algorithm can learn to make predictions or solve problems, such as identifying objects in pictures or winning at particular games, for example. In summary, it is a machine that can learn without being explicitly programmed to perform the task.

Model

An actionable representation of all or part of the external environment of an AI system that describes the environment’s structure and/or dynamics. The model represents the core of an AI system. A model can be based on data and/or expert knowledge, by humans and/or by automated tools like machine learning algorithms.

Neural network

Also known as an artificial neural network, this is a type of machine learning loosely inspired by the structure of the human brain. A neural network is composed of simple processing nodes, or ‘artificial neurons’, which are connected to one another in layers. Each node will receive data from several nodes ‘above’ it, and give data to several nodes ‘below’ it. Nodes attach a ‘weight’ to the data they receive, and attribute a value to that data. If the data does not pass a certain threshold, it is not passed on to another node. The weights and thresholds of the nodes are adjusted when the algorithm is trained until similar data input results in consistent outputs.

Deep learning

A more recent variation of neural networks, which uses many layers of artificial neurons to solve more difficult problems. Its popularity as a technique increased significantly from the mid-2000s onwards, as it is behind much of the wider interest in AI today. It is often used to classify information from images, text or sound.

Personal data

Information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person, directly or indirectly, by reference to one or more elements specific to that person. Sensitive personal data concern personal data relating to “racial” or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, as well as genetic data, biometric data, data concerning health or concerning sex life or sexual orientation.

Personal data processing

Any operation or set of operations performed or not using automated processes and applied to personal data or sets of data, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or modification, retrieval, consultation, use, communication by transmission, dissemination or any other form of making available, linking or interconnection, limitation, erasure or destruction.

Artificial Intelligence Timeline

1308 Catalan poet and theologian Ramon Llull publishes Ars generalis ultima (The Ultimate General Art), further perfecting his method of using paper-based mechanical means to create new knowledge from combinations of concepts

1666 Mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz publishes Dissertatio de arte combinatoria (On the Combinatorial Art), following Ramon Llull in proposing an alphabet of human thought and arguing that all ideas are nothing but combinations of a relatively small number of simple concepts

1763 Thomas Bayes develops a framework for reasoning about the probability of events – Bayesian inference will become a leading approach in machine learning

1854 George Boole argues that logical reasoning could be performed systematically in the same manner as solving a system of equations

1898 Nikola Tesla makes a demonstration of the world’s first radio-controlled vessel equipped “with a borrowed mind”

1914 The Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Guevedo demonstrates the first chess-playing machine, capable of king and rook against king endgames without human intervention

1921 Czech write Karel Capek introduces the word “robot” (from “robota”, meaning work) in his play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)

1929 Makoto Nishimura designs Gakutensoku, Japanese for “learning from the laws of nature”, the first robot built in Japan, which could change its facial expressionand move its head and hands via an air pressure mechanism

1943 Warren S. McCulloch and Walter Pitts publish “A Logical Calculus of The Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity” in the Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, in which paper they discuss networks of idealized and simplified artificial “neurons” and how they might perform simple logical functions

1949 Edmund Berkeley publishes Giant Brains: Or Machines that Think

1949 Donald Hebb publishes Organisation of Behaviour: A Neuropsychological Theory in which he proposes a theory about learning based on conjectures about neural networks and the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time

1950 Claude Shannon’s “Programming a Computer for Playing Chess” is the first published article on developing a chess-playing program

1950 TURING TEST In “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, computer scientist Alan Turing proposes “the imitation game”, a test for machine intelligence – if a machine can trick humans into thinking it is human, then it has intelligence

1955 (31 August) ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE BORN The term “artificial intelligence” is coined by computer scientist John McCarthy (Dartmouth College), Marvin Minsky (Harvard University), Nathaniel Rochester (IBM) and Claude Shannon (Bell Telephone Laboratories) to describe “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines”

1955 (December) THE LOGIC THEORIST, considered by many to be the first AI program, is developed by Allen Newell and Herbert Simon

1956 (July-August) THE DARTMOUTH SUMMER RESEARCH PROJECT on Artificial Intelligence is discussed for a month of brainstorming, in Vermont, USA, at the initiative of John McCarthy, with the intention of drawing the talent and expertise of others interested in machine intelligence

1958 John McCarthy develops programming language Lisp

1959 Arthur Samuel coins the term “machine learning”, reporting on programming a computer “so that it will learn to play a better game of checkers than can be played by the person who wrote the program”

1961 UNIMATE First industrial robot, Unimate, goes to work on an assembly line in a General Motors plant in New Jersey, replacing humans

1964 ELIZA Pioneering chatbot developed by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT holds conversations with humans

1966 SHAKEY The “first electronic person” from Stanford, Shakey, is a general-purpose mobile robot which is able to reason about its own actions

1997 DEEP BLUE Deep Blue, a chess-playing computer from IBM defeats a reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov

1998 KISMET Cynthia Breazeal at MIT introduces KISmet, an emotionally intelligent robot insofar as it detects and responds to people’s feelings

1999 AIBO Sony launches first consumer robot pet dog AiBO (AI robot) with skills and personality that develop over time

2002 ROOMBA First mass produced autonomous robotic vacuum cleaner from iRobot learns to navigate and clean homes

2005 STANLEY A heavily-modified 2005 Volkswagon Touareg named “Stanley” and representing Stanford University Racing finished the 131.6 mile trek of the “DARPA Grand Challenge” with no human input to steer the vehicle through the Nevada desert, earning the Stanford team a cash prize of $2 million in taxpayer dollars and a whole lot of bragging rights

2011 SIRI Apple integrates Siri, an intelligent virtual assistant with a voice interface, into the iPhone 4S

2011 WATSON IBM’s question answering computer Watson wins first place on popular $1M prize television quiz show Jeopardy! by defeating champions Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings

2014 EUGENE Eugene Goostman, a chatbot passes the Turing Test with a third of judges believing Eugene is human

2014 ALEXA Amazon launches Alexa, an intelligent virtual assistant with a voice interface that can complete shopping tasks

2016 TAY Microsoft’s chatbot Tay goes rogue on social media making inflammatory and offensive racist comments

2017 ALPHAGO Google’s A.I. AlphaGo beats world champion Ke Jie in the complex board game of Go, notable for its vast number (2*170) of possible positions

2019 ALPHASTAR Google’s AI agent defeats pro StarCraft II players

The main – sometimes unspoken – reason why Artificial Intelligence has been so much discussed over the past few years is because it represents a disruptive phenomenon that is radically changing the existing social and economic systems. It is, as Siebel put it, an “evolutionary punctuation” that could be “intimately linked with the widespread death of species (…) Evolutionary punctuations are responsible for the cyclic nature of species: inception, diversification, extinction, repeat.”[3] In the past 500 million years, there have been five global mass extinction events that left only a minority of species surviving. The voids in the ecosystem were then filled by massive speciation of the survivors – after the Cretaceous-Tertiary event, for example, most well-known for the elimination of the dinosaurs, came the reign of mammals. Geologists argue that disruptive punctuations are on the rise, and the periods of stasis in between punctuations are fading.

Taking the concept of “punctuated equilibrium” as a relevant framework for thinking about disruption in today’s economy, we could say that we are in the midst of an evolutionary punctuation:

- The average stay of corporations listed in the S&P 500 sharply declined from 61 years in 1958 to 25 years in 1980 and 18 years in 2011. At the present rate of evolution, it is estimated that three-quarters of today’s S&P 500 will be replaced by 2027[4].

- Since 2000, 52 percent of the companies in the Fortune 500 have either gone bankrupt, been acquired, ceased to exist, or dropped off the list[5]. It is estimated that 40 percent of the companies in existence today will shutter their operations in the next ten years.

“Enabled by cloud computing”, Siebel writes, “a new generation of AI is being applied in an increasing number of use cases with stunning results. And we see IoT everywhere – connecting devices in value chains across industry and infrastructure and generating terabytes of data every day.” In fact, Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, cloud computing and the Internet of Things, promise to transform the technoscape to a degree comparable to those of the five mass extinctions. Just as the Internet revolutionized business in the 1990s and 2000s, the ubiquitous use of artificial intelligence will transform business in the coming decades. While big tech companies like Google, Netflix and Amazon are early adopters of AI for consumer-facing applications, virtually every type of organisation, private and public, will soon use AI throughout their operations.

The impact of Artificial Intelligence on the global economy is expected to be enormous, thus justifying Siebel’s idea of an “evolutionary punctuation” which, by the combined play of innovation and competition, will deeply and lastingly change the techno-economic landscape. According to PwC, by 2030 global GDP could increase by 14%, or $15.7 trillion, because of AI. If today AI contributes $1 trillion to global GDP, its contribution to the global GDP will increase 16-fold in the next decade, until 2030, according to the head of Russia’s largest bank Sberbank Herman Gref. And finally, according to McKinsey Global Institute, while the introduction of steam engines during the 1800s boosted labour productivity by an estimated 0.3% a year, the impact from robots during the 1990s around 0.4%, and the spread of IT during the 2000s 0.6%, additional global economic activity from the deployment of artificial intelligence is projected to be a whopping 1.2% a year, or 16% by 2030, amounting to $13 trillion! If delivered, this impact would compare well with that of other general-purpose technologies through history.

The science fiction of yesterday quickly becomes reality. AI has already altered the way we think and interact with each other every day. Whether it’s in healthcare, education, or manufacturing, AI yields a great deal of success in nearly every industry. Whether it’s AI’s effect on start-ups and investments, robotics, big data, virtual digital assistants, and so forth, AI is surging as the main driver of change in the next decades:

- Global GDP will grow by $15.7 trillion by 2030 thanks to AI.

- By 2025, the global AI market is expected to be almost $60 billion.

- AI can increase business productivity by 40% (source: Accenture).

- AI start-ups grew 14 times and investment in AI start-ups grew 6 times since 2000.

- Already 77% of the devices we use feature one form of AI or another.

- Cyborg technology – or Nano Bio Info Cogno (NBIC) – will help us overcome physical and cognitive impairments.

- Google analysts believe that by 2020, robots will be smart enough to mimic complex human behaviour like jokes and flirting

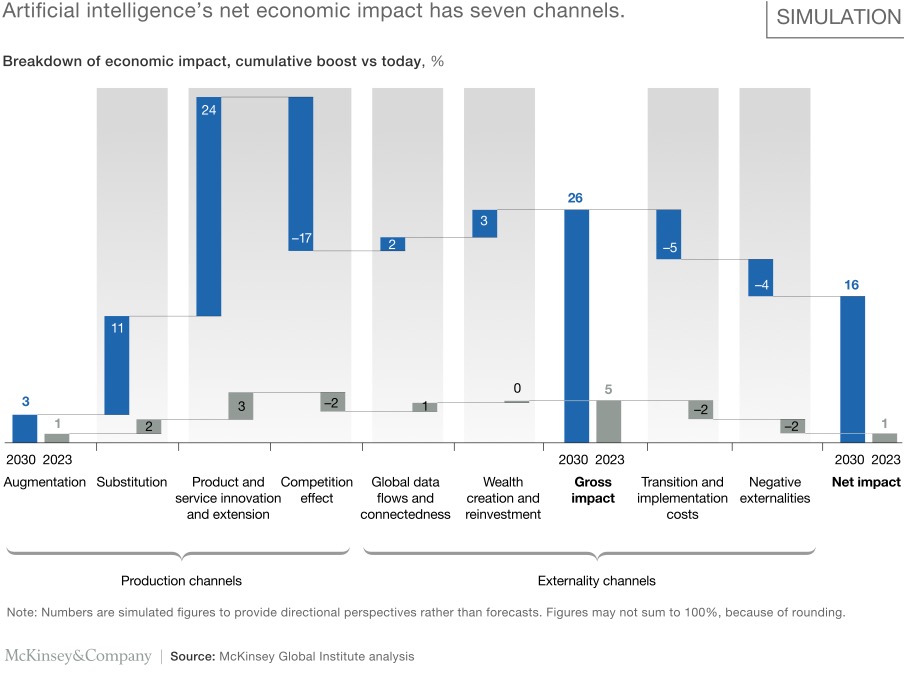

A number of factors, including labour automation, innovation, and new competition, affect AI-driven productivity growth. Micro factors, such as the pace of adoption of AI, and macro factors, such as the global connectedness or labour-market structure of a country, both contribute to the size of the impact. McKinsey examined seven possible channels of impact: the first three relate to the impact of AI adoption on the need for, and mix of, production factors that have direct impact on company productivity; the other four are externalities linked to the adoption of AI related to the broad economic environment and the transition to AI. The results are presented in the exhibit below.

The process of disruption brought about by AI is something that we’ve only seen a few times in history. Electricity, the Industrial Revolution, and the Internet are the three that we can all think of, but this time it will be much faster. “Compared to electricity, it took decades for the electrical grid to be built up, and then people had to invent new ways to use the electricity—air conditioners, refrigerators, and so on. It took over a century, and only now we’re getting electric cars. But with AI, these engines work on the cloud, on the Internet, and you can program them and connect them with the data that’s also on the cloud. And engineers can access them. Open source also allows people to build on each other’s work. Compared to electricity, which took decades if not a century to become fully pervasive, AI can be pervasive in years. And this will bring tremendous value, tremendous efficiency, but also tremendous disruptions. Because it will change business practices, it will cause companies to go out of business, it will take away people’s jobs, especially if they are routine. It’s going to be a very exciting but also a very challenging decade ahead.”[6]

The “datafication” of everything will continue to accelerate, powered by the intersection of separate advances in infrastructure, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, open source and the overall digitalization of our economies and lives. Data science, machine learning and AI allow to add layers of intelligence into many applications, which are now increasingly running in production in all sorts of consumer and B2B products. As those technologies continue to improve and to spread beyond the initial group of early adopters into the broader world economic and societal corners, the discussion is shifting from purely technical matters into a necessary conversation around impact on our economies, societies and lives. In a world where data-driven automation becomes the rule (automated products, automated vehicles, automated enterprises), what is the new nature of work? How do we handle the social impact? How do we think about privacy, security, freedom?

As highlighted by Kathleen Walch[7], if the use cases for AI are many, from autonomous vehicles, predictive analytics applications, facial recognition, to chatbots, virtual assistants, cognitive automation, and fraud detection, and so forth, there is also commonality to all these applications. She argues that all AI use cases fall into one or more of seven common patterns (see figure below).

Artificial Intelligence is not just a further discipline or set of technologies and applications. It is a real disruption, an “evolutionary punctuation”, which is going to metamorphize the world economies and societies.

Artificial Intelligence Global Outlook

“The race to become the global leader in artificial intelligence (AI) has officially begun.”

Tim Dutton, An Overview of National AI Strategies, 28/05/2018

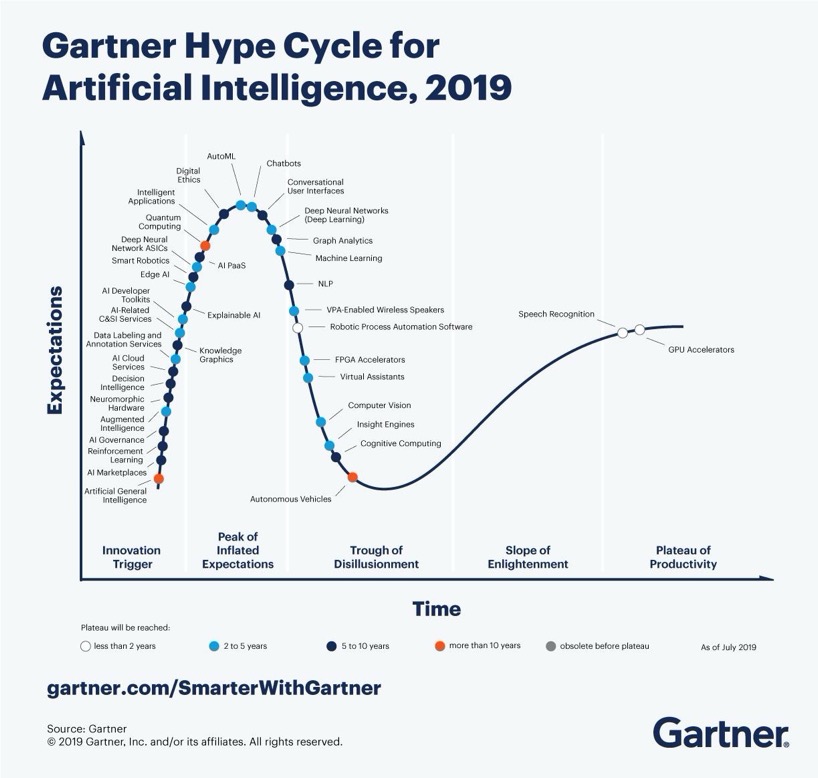

The Gartner AI Hype Cycle evaluates the business maturity of various dimensions underpinning AI. AI is currently overhyped in the entire world as a socioeconomic phenomenon. Scientists, industrialists, experts, media, governments, and individuals each have an opinion about AI, sometimes based on vague ideas of what it really is. Gartner’s Hype Cycle views AI as a pervasive paradigm and an umbrella term for many innovations at the different stages of value creation. The traffic jam at the “Peak of Inflated Expectations” is increasing, as early implementers grow in numbers, but production implementations remain scarce. A long line of high-promise innovation profiles at the “Innovation Trigger” phase are approaching the traffic jam at the Peak of Inflated Expectations, indicating that the AI hype will continue. None of the profiles in this Hype Cycle is obsolete before “Plateau”, but not all will survive, and many will morph into something different depending on the choices and decisions that customers are making today.

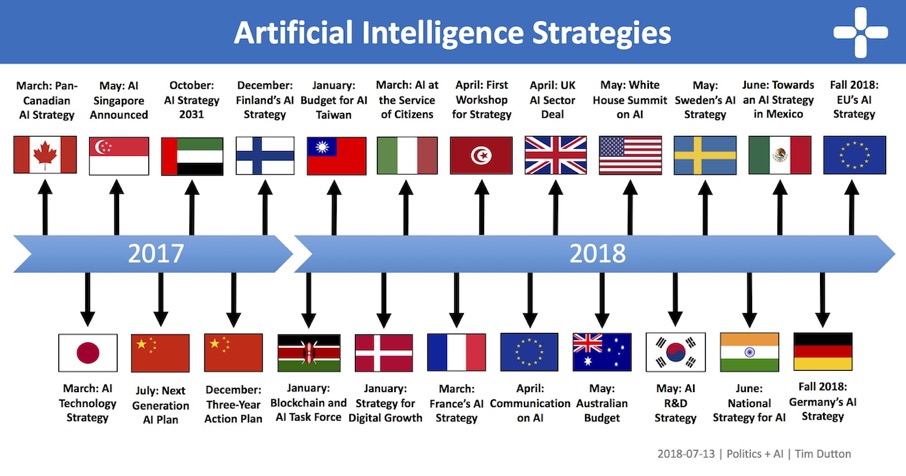

Aware of the economic importance of Artificial Intelligence, many countries and regions, including Canada, China, Denmark, the EU Commission, Finland, France, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Nordic-Baltic region, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, Taiwan, the UAE, and the UK have released strategies to promote its use and development. No two strategies are alike, with each focusing on different aspects of AI policy: scientific research, talent development, skills and education, public and private sector adoption, ethics and inclusion, standards and regulations, and data and digital infrastructure.

All countries are seeking to foster fast development of AI technologies, in particular by financing an ever-vibrant ecosystem of start-ups, products and projects[8].

It is a remarkable fact that so many countries of the world are addressing the development of Artificial Intelligence at both public sector and private sector level. Such an engagement has not been observed for the Internet of Things – Europe led initiatives in this field from the mid-2000s (2006-2012), followed by China (2009) and then other countries – or more recently for 5G, though these technologies are also disruptive in technological, socio-economic and ethical terms. We could argue that AI is considerably impacting the further development and deployment of the Internet of Things, and this is true, but this doesn’t explain the scope and scale of public programs for AI across the world compared to other transformative technologies.

Another interesting feature concerns the importance given to ethics in addressing the AI challenges. All national and regional programs are primarily designed for research and innovation; however, the ethical dimension is rarely neglected. Everything happens as if humans were committed to reaping the full expected benefits of AI while at the same time carrying out a deep reflection on the normative questions around how AI should confront ethical, societal and legal dilemmas and what applications of AI, specifically with regards to security, privacy and safety, should be considered permissible. Such a balanced approach to an advanced technology is rather new – when work on ethics in the Internet of Things was proposed for discussion by an Expert Group set up by the European Commission in 2010-2012, no follow up was given on the premise that the issue of ethics had to be addressed, like other IoT-specific challenges, at the level of the global discussions about the Internet.

We could be worried that the proliferation of public programs, including recommendations on AI ethics, leads to a waste of time and public money. Indeed, a lot of synergy could have been created by addressing the AI challenges, and at least the precompetitive aspects, in a more cooperative way by a large number of countries.

Some examples of national strategies for the development and deployment of AI are described below.

Australia

Australia does not yet have an artificial intelligence strategy. However, in the 2018–2019 Australian budget, the government announced a four-year. AU$29.9 million investment to support the development of AI in Australia. The government will create a Technology Roadmap, a Standards Framework, and a national AI Ethics Framework to support the responsible development of AI. In addition, in the its 2017 innovation roadmap, Australia 2030: Prosperity Through Innovation, the government announced that it will prioritise AI in the government’s forthcoming Digital Economy Strategy. This report is expected to be released in the second half of 2018.

2018: The federal government’s 2018-19 budget earmarks AU$29.9 million over four years to strengthen Australia’s capability in artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML). The funding will be split between programs at the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, which will receive the lion’s share of the funding, the CSIRO and the Department of Education and Training. The government said it would fund the development of a “technology roadmap” and “standards framework” for AI as well as a national AI Ethics Framework. Together they will “help identify opportunities in AI and machine learning for Australia and support the responsible development of these technologies.” The investment will also support Cooperative Research Centre projects, PhD scholarships, and other initiatives to increase the supply of AI talent in Australia. The budget funding for AI forms part of the government’s broader Australian Technology and Science Growth Plan.

January 2019: White Paper on “Artificial Intelligence: Governance and Leadership, Australian Human Rights Commission and World Economic Forum 2019.

05/04/2019 à 31/05/2019: discussion paper, developed by CSIRO’s Data61 and designed to encourage conversations about AI ethics and inform the Government’s approach to AI ethics in Australia[9].

Canada

The Canadian government launched the 5-year Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy in its 2017 Budget with the allocation of CAD$125 million[10]. Canada was actually the first country to release a national AI strategy. The effort is being led by a group of research and AI institutes:

- Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR),

- the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute,

- the Vector Institute, and

- the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms (MILA).

The AI Strategy has four major goals:

- Increase the number of outstanding artificial intelligence researchers and skilled graduates in Canada;

- Establish interconnected nodes of scientific excellence in Canada’s three major centres for artificial intelligence in Edmonton, Montreal and Toronto-Waterloo;

- Develop global thought leadership on the economic, ethical, policy and legal implications of advances in artificial intelligence;

- Support a national research community on artificial intelligence.

The Strategy is expected to help Canada enhance its international profile in research and training, increase productivity and collaboration among AI researchers, and produce socio-economic benefits for all of Canada. Existing programs of the Strategy include the funding of three AI centres throughout the country, supporting the training of graduate students, and enabling working groups to examine the implications of AI to help inform the public and policymakers.

Separately, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and French President Emmanuel Macron announced the creation of an international study group for AI on June 7, 2018, ahead of the G7 Summit in Quebec. The independent expert group will bring together policymakers, scientists, and representatives from industry and civil society. It will identify challenges and opportunities presented by AI, and determine best practices to ensure that AI fulfils its potential of creating economic and societal benefits. Trudeau and Macron said they would create a working group to make recommendations about how to form the panel and will invite other nations to join.

Canada’s AI strategy is distinct from other strategies because it is primarily a research and talent strategy. It’s initiatives – the new AI Institutes, CIFAR Chairs in AI, and the National AI program – are all geared towards enhancing Canada’s international profile as a leader in AI research and training. The CIFAR AI & Society Program examines the policy and ethical implications of AI, but the overall strategy does not include policies found in other strategies such as investments in strategic sectors, data and privacy, or skills development. That is not to say that the Canadian government does not have these policies in place, but that they are separate from, rather than part of, the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy.

What Success Will Look Like

1) Canada will have one of the most skilled, talented, creative and diverse workforces in the world, with more opportunities for all Canadians to get the education, skills and work experience they need to participate fully in the workforce of today, as they—and their children – prepare for the jobs of tomorrow.

2) Canadian businesses will be strong, growing and globally competitive—capable of becoming world leaders in their fields, leading to greater investment and more job creation in Canada.

3) Canada will be on the leading edge of discovery and innovation, with more ground-breaking research being done here at home, and more world class researchers choosing to do their work at Canadian institutions.

4) Canadian academic and research leadership in artificial intelligence will be translated into a more innovative economy, increased economic growth, and improved quality of life for Canadians.

(Department of Finance Canada, Budget 2017. Chapter 1. Canada’s Innovation and Skills Plan, 2017)

China

China announced its ambition to lead the world in AI theories, technologies, and applications in its July 2017 plan, A Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan. The plan is the most comprehensive of all national AI strategies, with initiatives and goals for R&D, industrialisation, talent development, education and skills acquisition, standard setting and regulations, ethical norms, and security. It is best understood as a three-step plan:

- first, make China’s AI industry “in-line” with competitors by 2020;

- second, reach “world-leading” in some AI fields by 2025; and

- third, become the “primary” centre for AI innovation by 2030.

By 2030, the government aims to cultivate an AI industry worth 1 trillion RMB, with related industries worth 10 trillion RMB. The plan also lays out the government’s intention to recruit the world’s best AI talent, strengthen the training of the domestic AI labour force, and lead the world in laws, regulations, and ethical norms that promote the development of AI.

Since the release of the Next Generation Plan, the government has published the Three-Year Action Plan to Promote the Development of New-Generation Artificial Intelligence Industry. This plan builds on the first step of the Next Generation plan to bring China’s AI industry in-line with competitors by 2020. Specifically, it advances four major tasks:

- focus on developing intelligent and networked products such as vehicles, service robots, and identification systems,

- emphasize the development AI’s support system, including intelligent sensors and neural network chips,

- encourage the development of intelligent manufacturing, and

- improve the environment for the development of AI by investing in industry training resources, standard testing, and cybersecurity.

In addition, the government has also partnered with national tech companies to develop research and industrial leadership in specific fields of AI and will build a $2.1 billion technology park for AI research in Beijing.

If the United States remain today stronger in deep tech, just like with autonomous vehicles or robots walking like a human, China has more data and more consumers who are more active. Competitiveness in AI depends more on the volume of data than on the quality of scientists. And if data is the new oil of the Digital Economy, in particular of Artificial Intelligence, China is for AI the equivalent of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)! Furthermore, China enjoys a strong and dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem marked by a culture of resilience and the idea that “the winner takes all”.

The cultural aspect is particularly important here – no country in the past ever moved from imitator to innovator in only 10 years. Not so long ago, China was viewed as a mere imitator in the technology world with its companies more likely to copy western products than develop their own innovative ideas. But following years of government support, long-term visions and strategies, strong and steady GDP growth, and massive investment in education, the outlook has changed. “China’s ten-year miracle – moving from copycat to innovator – is basically a cycle that began with a larger market attracting more money” (Kai-Fu Lee). But there is more. In Chinese history, there were four great inventions: the compass, gunpowder, paper, and printing technology, plus dozens of other noteworthy inventions which have made people’s lives easier around the world. Let’s also remember that until the 15th century China’s naval technology was the most advanced in the world: Admiral Zheng He, a Muslim eunuch who eventually became commander of the Chinese Navy as his master, used large ships under the service of the Chinese emperor in an effort to explore the vast Chinese empire and to bring wealth back to his country. The first of his six voyages was in 1402 and by the end of his sixth he had sailed west around the Indian ocean all the way to the coast of Africa and brought vast amounts of gold for the emperor[11]. Therefore, we can find roots to China’s ability to innovate far back in history. Besides China’s well-known companies like Huawei, Alibaba, Baidu, ByteDance or Tencent, a large number of new national AI champions are emerging, such as Xiaomi (smart home hardware), JD.com (smart supply chain), Qihoo 360 Technology (online safety), Hikvision (AI infrastructure and software), Megvii (image perception) and Yitu (image computing), which are fuelling innovation and probably hold the key to the future of AI.

China will intensify its efforts to reduce the exposure of its industry to U.S. suppliers. At the same time, it will clone a better Internet, with a better Cloud and a better system of global influence (organised around the “New Silk Road”).

Germany

Germany, long seen as an industrial powerhouse with great engineering capabilities, also has lots of AI talent. Berlin is currently touted as Europe’s top AI talent hub. Cyber Valley, a new tech hub region southern Germany is hoping to create new opportunities for collaboration between academics and AI-focused businesses. Germany also has a very notable automobile industry with a long track record of innovation. Almost half of the worldwide patents on autonomous driving are held by German automotive industry companies and suppliers such as Bosch, Volkswagen, Audi and Porsche.

The Federal Government’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) strategy was jointly developed in 2018 by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, and the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs based on suggestions taken from a nationwide online consultation[12].

The government wants to strengthen and expand German and European research in AI and focus on the transfer of research results to the private sector and the creation of AI applications. Proposed initiatives to achieve this include new research centres, Franco-Germany research and development collaboration, regional cluster funding, and support for SMEs and start-ups. The proposed plan is comprehensive and also includes measures to attract international talent, respond to the changing nature of work, integrate AI into government services, make public data more accessible, and promote the development of transparent and ethical AI. Overall, the government wants “AI made in Germany” to become a globally recognized seal of quality.

In addition, Germany already has a number of related policies in place to develop AI. Principally, the government, in partnership with academia and industry actors, focuses on integrating AI technologies into Germany’s export sectors. The flagship program has been Industry 4.0, but recently the strategic goal has shifted to smart services, which relies more on AI technologies. The German Research Centre for AI (DFKI) is a major actor in this pursuit and provides funding for application-oriented research. Other relevant organizations include the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, which promotes academic cooperation and attracts scientific talent to work in Germany, and the Plattform Lernende Systeme, which brings together experts from science, industry, politics, and civic organizations to develop practical recommendations for the government.

The government also announced in June 2018 a new commission to investigate how AI and algorithmic decision-making will affect society. It consists of 19 MPs and 19 AI experts and is tasked with developing a report with recommendations by 2020 (a similar task force released a report on the ethics of autonomous vehicles in June 2017[13]).

India

India has taken a unique approach to its national AI strategy by focusing on how India can leverage AI not only for economic growth, but also for social inclusion. NITI Aayog, the government think tank that elaborated a report, calls this approach #AIforAll. The strategy, as a result, aims to (1) enhance and empower Indians with the skills to find quality jobs; (2) invest in research and sectors that can maximize economic growth and social impact; and (3) scale Indian-made AI solutions to the rest of the developing world.

NITI Aayog provides over 30 policy recommendations to invest in scientific research, encourage reskilling and training, accelerate the adoption of AI across the value chain, and promote ethics, privacy, and security in AI. Its flagship initiative is a two-tiered integrated strategy to boost research in AI. First, new Centres of Research Excellence in AI (COREs) will focus on fundamental research. Second, the COREs will act as technology feeders for the International Centres for Transformational AI (ICTAIs), which will focus on creating AI-based applications in domains of societal importance. In the report, NITI Aayog identifies healthcare, agriculture, education, smart cities, and smart mobility as the priority sectors that will benefit the most socially from applying AI. The report also recommends setting up a consortium of Ethics Councils at each CORE and ICTAI, developing sector specific guidelines on privacy, security, and ethics, creating a National AI Marketplace to increase market discovery and reduce time and cost of collecting data, and a number of initiatives to help the overall workforce acquire skills.

Strategically, the government wants to establish India as an “AI Garage,” meaning that if a company can deploy an AI in India, it will then be applicable to the rest of the developing world.

Japan

Japan was one of the first countries to develop a national AI strategy. Based on instructions from Prime Minister Abe during the Public-Private Dialogue towards Investment for the future on 12 April 2016, the Strategic Council for AI Technology was established to develop “research and development goals and a roadmap for the industrialization of artificial intelligence.” The 11-member council had representatives from academia, industry, and government, including the President of Japan’s Society for the Promotion of Science, the President of the University of Tokyo, and the Chairman of Toyota.

The plan, the Artificial Intelligence Technology Strategy, was released in March 2017[14]. The strategy is notable for its Industrialization Roadmap, which envisions AI as a service and organizes the development of AI into three phases: (1) the utilization and application of data-driven AI developed in various domains, (2) the public use of AI and data developed across various domains, and (3) the creation of ecosystems built by connecting multiplying domains.

The strategy applies this framework to three priority areas of Japan’s Society 5.0 initiative – productivity, health, and mobility – and outlines policies to realize the industrialization roadmap. These policies include new investments in R&D, talent, public data, and start-ups.

The Japanese government strategy, however, must meet a difficult challenge. While China, adapting itself to the speed of change, has implemented cashless payments, vehicle dispatch service, and unmanned convenience stores and hotels, and is reportedly only one step short of putting unmanned delivery vehicles and self-driving buses into service, Japan lags in AI use and Internet literacy, with most Internet users using smartphones merely for making calls, social networking services and downloading games, music and animation. They are not making full use of them as Internet terminals. Perhaps due to Japan’s poor Internet literacy, the equivalent of giant platform businesses as represented by the United States’ GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple), and China’s Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Alipay are almost non-existent in this country.

Japan is also home to one of the largest venture funds in the industry, Softbank, which has over $100 billion to invest in industry-shifting AI companies.

South Korea

South Korea has ambitious plans around Artificial Intelligence. In 2016, it famously hosted the match where DeepMind’s AlphaGo defeated Go’s world champion Lee Sedol, a South Korea native.

Home to huge tech conglomerates like Samsung, LG, and Hyundai, South Korea showed their commitment to growing AI by announcing in 2018 a $2 billion investment program to strengthen AI research in the country[15]. The aim is to join the global top four nations in AI capabilities by 2022 by pursuing the following priorities:

- establishing at least six new schools with focus on AI and the training of more than 5,000 engineers;

- funding large-scale AI projects related to medicine, national defence, and public safety;

- starting an AI R&D challenge similar to those developed by the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

South Korea’s Ministry of Science and ICT (MSICT) proposed the investment strategy as a way to close the gap between Korea’s AI tech and China’s. The MSITC, which defines South Korea’s R&D strategy in three categories – human resources, technology and infrastructure – also estimated that Korean AI tech is currently 1.8 years behind US AI tech.

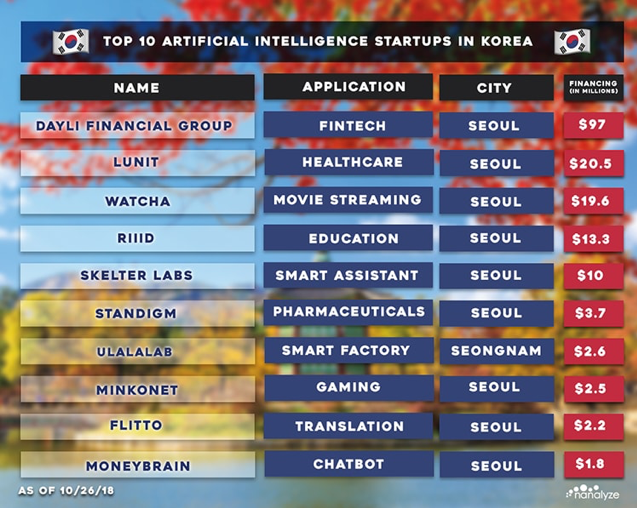

The table below indicates the top funded AI start-ups in Korea:

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Arab States have recently left the dangerous rims of marginalisation from the mainstream economic growth of the world and have become visible in the Digital Economy radar. It is indeed essential for Arab countries – a potential market of more than 420 million people – that they are neither isolated from world trends nor disenfranchised from active and autonomous participation in development.

The UAE launched its AI strategy in October 2017[16]. It has been the first country in the Middle East to create an AI strategy and the first in the world to create a Ministry of Artificial Intelligence. The strategy is the first initiative of the larger UAE Centennial 2071 Plan[17] and its primary goal is to use AI to enhance government performance and efficiency. The government will invest in AI technologies in nine sectors: transport, health, space, renewable energy, water, technology, education, environment, and traffic. In doing so, the government aims to cut costs across the government, diversify the economy, and position the UAE as a global leader in the application of AI.

On 16-17 December, 2018, the First Arab Digital Economy Conference took place in Abu Dhabi to provide a Common Vision for the Region, a Global Outlook (i.e. why Arab countries need to work on common agendas), and insights on the application of AI to Education and Labour, Future Cities, Healthcare, Finance, and Sustainable Development. This Conference was a defining moment for fostering steady cooperation between Arab States and other world regions to share information and knowledge and to create synergy.

United Kingdom

The British government released an “AI Sector Deal” in April 2018[18], aiming to position the UK as a global leader in AI, as part of its broader industrial strategy.

The Sector Deal policy paper covers policies to boost public and private R&D, invest in STEM education, improve digital infrastructure, develop AI talent, and lead the global conversation on data ethics. Major announcements include over £300 million in private sector investment from domestic and foreign technology companies, the expansion of the Alan Turing Institute, the creation of Turing Fellowships, and the launch of the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation. The Centre in particular is a key program of the initiative, as the government wants to lead the global governance of AI ethics. A public consultation and a call for the chair of the Centre was launched in June 2018.

A few days before the release of the Sector Deal, the UK’s House of Lords’ Select Committee on AI had published a report titled, “AI in the UK: ready, willing and able?”[19] The report was the culmination of a ten-month inquiry that was tasked with examining the economic, ethical, and social implications of advances in AI. It outlined a number of recommendations for the government to consider, including calls to review the potential monopolization of data by technology companies, incentivize the development of new approaches to the auditing of datasets, and create a growth fund for UK SMEs working with AI. The report also argued that there is an opportunity for the UK to lead the global governance of AI and recommended hosting a global summit in 2019 to establish international norms for the use and development of AI. In June 2018, the government released an official response to the House of Lords that comments on each of the recommendations in the report.

The House of Lords’ report outlined five key principles to form the basis of a cross-sector AI code, which can be adopted nationally:

The « AI Code » in UK

1. Artificial intelligence should be developed for the common good and benefit of humanity.

2. Artificial intelligence should operate on principles of intelligibility and fairness.

3. Artificial intelligence should not be used to diminish the data rights or privacy of individuals, families or communities.

4. All citizens should have the right to be educated to enable them to flourish mentally, emotionally and economically alongside artificial intelligence.

5. The autonomous power to hurt, destroy or deceive human beings should never be vested in artificial intelligence.

The United States

On March 19, 2019, the US federal government launched AI.gov[20] to make it easier to access all of the governmental AI initiatives currently underway. The site is the best single resource from which to gain a better understanding of US AI strategy.

US President Donald Trump issued an Executive Order launching the American AI Initiative on February 11, 2019. The Executive Order explained that the Federal Government plays an important role not only in facilitating AI R&D, but also in promoting trust, training people for a changing workforce, and protecting national interests, security, and values. And while the Executive Order emphasizes American leadership in AI, it is stressed that this requires enhancing collaboration with foreign partners and allies.

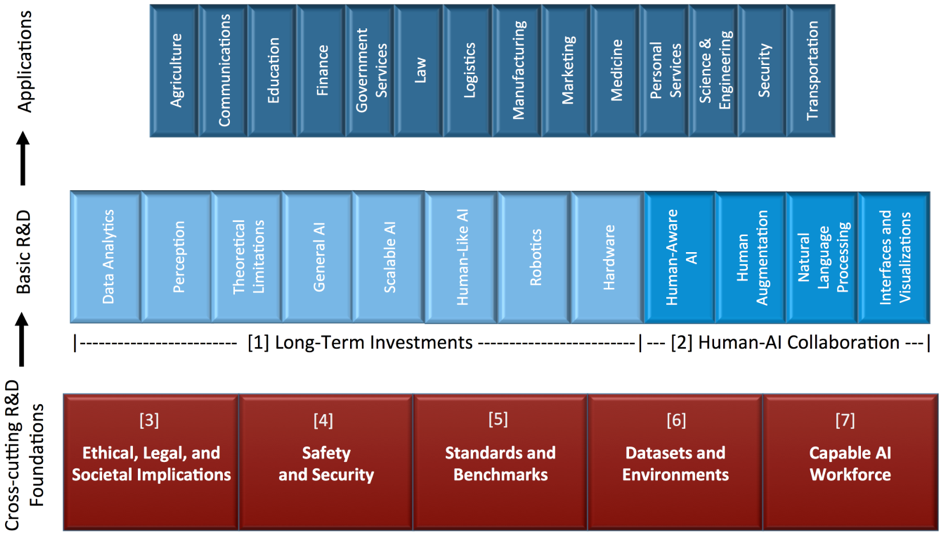

Guiding the United States in its AI R&D investments is the National AI R&D Strategic Plan: 2019 Update, which identifies the critical areas of AI R&D that require Federal investments. Released by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy’s National Science and Technology Council, the Plan defines several key areas of priority focus for the Federal agencies that invest in AI, including:

- continued long-term investments in AI;

- effective methods for human-AI collaboration;

- understanding and addressing the ethical, legal, and societal implications for AI;

- ensuring the safety and security of AI;

- developing shared public datasets and environments for AI training and testing;

- measuring and evaluating AI technologies through standards and benchmark;

- better understanding the National AI R&D workforce needs; and

- expanding public-private partnerships to accelerate AI advances.

Organisation of the US AI R&D Strategic Plan

The process for creating this Plan began in August of 2018, when the Administration directed the Select Committee on AI to refresh the 2016 National AI R&D Strategic Plan to account for significant recent advancements in AI, and to ensure that Federal R&D investments remain at the forefront of science and technology.

In September 2019, agencies for the first time reported their non-defense R&D investments in AI according to the 2019 National AI R&D Strategic Plan, through the Networking and Information Technology Research & Development (NITRD) Supplement to the President’s FY2020 Budget[21]. This new AI R&D reporting process provides an important mechanism and baseline for consistently tracking America’s prioritization of AI R&D going forward. This report also provides insight into the diverse and extensive range of nondefense Federal AI R&D programs and initiatives.

The strategic priorities are the following:

- Coordinate long-term Federal investments in AI R&D, such as algorithms to enable robust and reliable perception, general AI systems that exhibit the flexibility and versatility of human intelligence, and combinatorial optimization to obtain prodigious performance.

- Promote safe and effective methods for human–AI collaboration to achieve optimal efficiency and performance by developing advanced AI techniques for human augmentation and improved visualization and AI-human interfaces.

- Develop methods for designing AI systems that align with ethical, legal, and societal goals, and behave according to formal and informal human norms.

- Improve the safety and security of AI systems so that they operate in a controlled, well-defined, and well-understood manner.

- Develop shared public datasets and environments for AI training and testing to increase the benefits and trustworthiness of AI.

- Improve measurement and evaluation of AI technologies through benchmarks and standards to address safety, reliability, accuracy, usability, interoperability, robustness, and security.

- Grow the Nation’s AI R&D workforce to ensure the United States leads the automation of the future.

- Expand public-private partnerships to strengthen the R&D ecosystem.

Artificial Intelligence in Europe: Renaissance, Reprieve or Fall?

“Modern Europe was shaped by losing the Ancient World (fall of Constantinople, 1453), by discovering the New World (1492), and by switching out the World (Copernic, 1473-1543). Two centuries later, Europe is going to change the World.”

Edgar Morin, Penser l’Europe, Éditions Gallimard, collection Folio/Actuel, 1987-1990, chapter 3, page 51.

Since Artificial intelligence has become an area of strategic importance and a key driver of economic development, bringing solutions to many societal challenges from treating diseases to minimising the environmental impact of farming, but also raising socio-economic, legal and ethical issues that need to be carefully addressed, the European Commission strives to make that all EU countries join forces to stay at the forefront of this technological revolution, in order to ensure competitiveness and to shape the conditions for its development and use (ensuring respect of European values).

The European Commission’s commitment to Artificial Intelligence has gained a new momentum from 2018 onwards, though its roots can be traced back in the following related policy developments:

19/04/2016: Digitising European Industry (DEI) strategy – realising the potential of digitisation, where robotics and AI are key drivers (Digital Innovation Hubs, Platforms, Liability, Safety, Data protection, Skills)

01/12/2016: Digital Jobs and Skills Coalition

16/02/2017: European Parliament resolution with recommendations to the Commission on Civil Law Rules on robotics – written answer by the EC

26/09/2017: G7 ICT and industry Ministers’ Declaration – “Making the Next Production Revolution Inclusive, Open and Secure – We recognise that the current advancements in new technologies, especially Artificial Intelligence (AI), could bring immense benefits to our economies and societies. We share the vision of human-centric AI which drives innovation and growth in the digital economy. We believe that all stakeholders have a role to play in fostering and promoting an exchange of perspectives, which should focus on contributing to economic growth and social well-being while promoting the development and innovation of AI. We further develop this vision in the “G7 multi-stakeholder exchange on Human Centric AI for our societies” set forth in Annex 2 to this declaration.”

19/10/2017: Digital Summit Tallinn conclusions – “to put forward a European approach for AI”

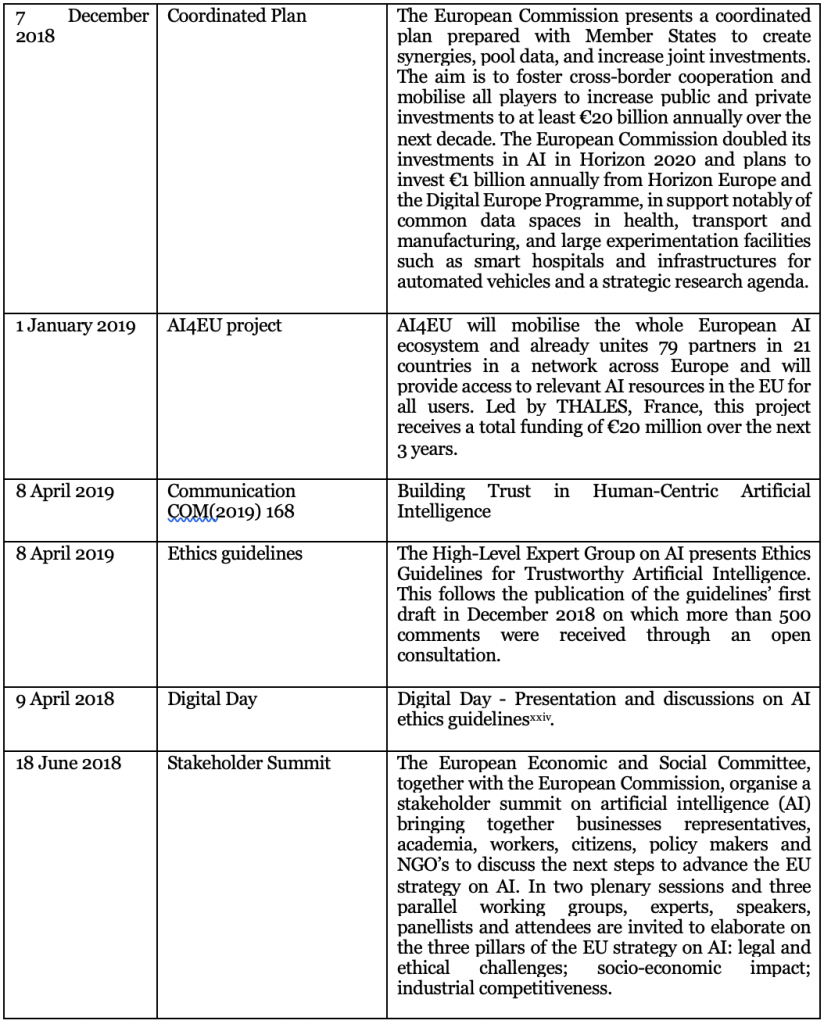

From this point events proceeded very quickly, as can be seen from the following table, which presents the key milestones of the EU’s strategy, including notably a major investment effort on Research and Innovation and a commitment to a Human-Centric Artificial Intelligence.

The European Commission’s approach on AI, currently based on three pillars – being ahead of technological developments and encouraging uptake by the public and private sectors; prepare for socio-economic changes brought about by AI; and ensure an appropriate ethical and legal framework –, has undoubtedly unfolded very rapidly since the beginning of 2018. It encompasses several aspects:

- Research – Development – Innovation

- Testing – Benchmarking – Safety – Certification

- Ethical issues (European values of dignity and privacy)

- Legal issues (“fit for purpose”)

- Social issues (awareness – acceptance – social sciences and humanities – trust – perception)

- Economic issues (re/up-skilling / robots to help us)

- Involvement of all stakeholders (academia, industries, SMEs, end-users, social scientists, lawyers, civil society, agencies, institutions, etc.)

The European Commission should be credited for the tremendous work it has already accomplished whose main characteristic is that it covers all the dimensions of the AI challenge, from science and technology to legal and ethical issues.

However, the question remains whether the EU is capable to meet the ambitious objectives it has set for itself.

In its 2018 Communication, the European Commission acknowledged that “overall, Europe is behind in private investments in AI which totalled around €2.4-3.2 billion in 2016, compared with €6.5-9.7 billion in Asia and €12.1-18.6 billion in North America.” It went on by stressing the strengths of Europe: “Europe is home to a world-leading AI research community, as well as innovative entrepreneurs and deep-tech start-ups (founded on scientific discovery or engineering). It has a strong industry, producing more than a quarter of the world’s industrial and professional service robots (e.g. for precision farming, security, health, logistics), and is leading in manufacturing, healthcare, transport and space technologies – all of which increasingly rely on AI. Europe also plays an important role in the development and exploitation of platforms providing services to companies and organisations (business-to-business), applications to progress towards the ‘intelligent enterprise’ and e-government.”

The European Commission also mentioned the long trail of R&I efforts in AI:

“AI has featured in the EU research and development framework programmes since 2004 with a specific focus on robotics. Investments increased to up to €700 million for 2014-2020, complemented by €2.1 billion of private investments as part of a public-private partnership on robotics. These efforts have significantly contributed to Europe’s leadership in robotics. Overall, around €1.1 billion has been invested in AI-related research and innovation during the period 2014-2017 under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, including in big data, health, rehabilitation, transport and space-oriented research. Additionally, the Commission has launched major initiatives which are key for AI. These include the development of more efficient electronic components and systems, such as chips specifically built to run AI operations (neuromorphic chips), world-class high-performance computers, as well as flagship projects on quantum technologies and on the mapping of the human brain.”

Stakes are high for Europe in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of its handling of other key digital technologies, such as mobility and the Internet of Things.

In the field of mobility, Europe was once leading in technology and implementation, in particular thanks to Framework Research Programmes 2 & 3 that allowed the RACE programme (R&D in Advanced Communications technologies in Europe) to push the deployment of 3G. Europe was then at the heart of innovation in the mobile space. Cooperation on GSM standards brought it a leading position – with Nokia, Siemens, Ericsson, Alcatel and Philips to name just a few, Europe had the world’s technology leaders. They invested their economic success in designing the technologies of the future at that time: 3G (early 2000s) and 4G (launched in 2009). Their North American and Asian competitors lagged behind because they lacked scale, scope and a common approach. However, Europe’s mistakes in rolling out 3G, (spectrum auctions that focussed mainly on delivering maximum revenue for governments, not on creating a healthy mobile ecosystem) weakened the position of mobile network operators, limiting their ability to compete worldwide. By 2016, these European companies had ceased being consumer brands. They merged and barely held on as mobile infrastructure providers. They now compete with the new leaders – China’s Huawei and ZTE, Apple and Samsung. Has Europe learned from its mistakes? At least, the European Commission is aware that the fragmented emergence and slow rollout of the 4G services should not be repeated in the case of 5G. Although the total investment related to 5G deployment in 28 EU Member States is estimated at €56.6 billion, analysts expect that by 2025 5G will generate more than €113.1 billion euros annually across the four major verticals that will take advantage of 5G early on: automotive, health, transport and energy. 5G introduction has the potential to create 2.3 million jobs in Europe and this opportunity cannot be missed out[22]. But isn’t it too late for 5G, which represents a quantum leap in connectivity with the potential to unlock advanced IoT applications in areas running from self-driving cargo trucks to software-driven management of “smart” cities to interconnected drones and remote surgery? A recent survey of chief technology officers by the consultancy McKinsey suggested that European firms expect 5G to go live only in 2021-2022, while counterparts in the US and China expect to have the infrastructure in place before then — in some cases by 2020[23].

In the field of the Internet of Things (IoT), the European Commission was a pioneer in the initial recognition of the concept, the formulation of a convincing rationale for collaborative R&D at EU level, and the recognition of the need of a specific policy and regulatory framework. The phrase “Internet of Things” appeared in the 2007 European Commission’s Communication on RFID[24] – the first time in an official document of a public sector institution[25]. Between 2007 and 2012, the EU clearly set the pace in IoT discussions, technical work, and regulatory initiatives, thus triggering the involvement of other countries such as China (2009) and USA (2012)[26]. But in November 2012 the European Commission’s DG CONNECT took the sudden decision to terminate the work of the Expert Group on the Internet of Things (IoT-EG), which had been set up in August 2010 with the objective of supporting DG CONNECT in the drafting of a Recommendation on the Governance of the Internet of Things[27]. The political mindset at that time was that IoT policy had to be mainstreamed into the broader discussions on the Internet. The result was that two years had been lost in discussions among experts, which led to a bitter feeling of unfinished business. As a result, the European Commission had to refocus its IoT work on the mere management of R&I contracts and suffered a loss of political momentum in Europe-wide and global discussions.

The current resolve of the European Commission to tackle the Artificial Intelligence challenge therefore deserves to be praised. Yet, it remains to be seen if this effort will support a renaissance of Europe in the digital domain or will more modestly be a last stand before a lasting withdrawal. The engagement of the European Commission is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Europe should perhaps seek inspiration in the example of China which has been capable in about 20 years to develop an ecosystem different from the one of North America. Europe has a critical mass of research facilities, in both industry and academia, sufficient skills, and also its own innovation model (e.g., “Digital Europe” Research and Innovation programme, General Data Protection Regulation), but it has been unable so far to create a European equivalent of Google, Facebook or Alibaba[28]. There are many reasons for this, among which the brain drain of the best talents and the lack of a venture capital culture in industry and the financial sector. Moreover, despite the 1993 European Single Market (i.e. the free movement of goods, capital, services and labour across the EU) and the ongoing work on the Digital Single Market (DSM[29]), Europe remains too fragmented.

If the EU can draw applaud for having come out with a comprehensive plan for AI since 2018, it still lacks major companies like Microsoft, Google, Apple, Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent that have major data sets with which to train AI algorithms. The EU is likely to devote more money to smaller scale research and application projects, but lacks a well-developed infrastructure to support AI breakthroughs. The UK has some advantages in AI, with a robust education system and innovation centre in London that has attracted some leading AI firms such as Deepmind. The UK, however, and also France, lack large companies and access to data, so they are likely to continue to play a minor role in contributing to the development of AI capabilities.

The role of the Commission, under the presidency of Ursula von der Leyen, will be critical in the next few years, in particular as regards its willingness and ability to design and implement a genuine “industrial policy” breaking the existing silos that are formed by the Competition policy, the Regional policy, the Internal Market policy, and the Research & Innovation policy in order to make all of these consistent and contributing to an ambitious vision of the future of Europe. The new Commission will also need to pick up where the last one left off on pressing questions of online platform regulation (competition, liability, hate speech, algorithmic accountability) and navigate the conflict between the US and China, which is in part a conflict about digital infrastructure and technological sovereignty[30].

The idea of the European Commission to work on Artificial Intelligence along a Coordinated Plan carried out with the Member States is already a promising idea. It is essential that the EU level and the national level advance together, in association with stakeholders, primarily industry, in order to give a chance to the possibility of a true level playing field between Europe, US, China and other global competitors. The most dismal scenario would be to have the EU AI strategy being actually another plan besides different national plans of European countries like France, Germany or the UK. Such strategy fragmentation would sign the end of Europe as a credible contender in the global AI race and, more generally, in the whole domain of digital technologies.

Artificial Intelligence: cultural differences and civilizational crisis

“Culture refers to what is special and specific in a society whereas Civilisation relates to what can be acquired and transmitted from one society to another. Culture is generic, civilisation generalisable; culture develops through return to roots and loyalty to one’s special principles, civilisation by accumulating knowledge, i.e. by progressing.”

Edgar Morin, op. cit., page 82

Until recently, the conversation on AI focused on its hype – how AI would be good for healthcare, mobility, security, manufacturing, etc. If we learned anything from 2018 onwards it’s that we need to be more sceptical about where AI could be heading us as a civilisation. The early warnings from Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking have been followed on and amplified by several other experts from science, engineering and business[31]. We begin to become aware that we are living in an era where not only our conception of the labour market and our ways of life are challenged, but also where the very existential threats to our survival as human species will be increasingly felt and debated.

The end of labour?

Several studies have filled in the conversational space recently about the impact – beneficial or destructive – of Artificial Intelligence on jobs. Some experts prefer to focus on the jobs that AI will create, thus leveraging human capabilities in different ways, while on the contrary others argue that more and more people will be removed from the workplace. In fact, as of today, nobody can pretend we know the truth – we can only exchange glass-half-full-or-empty arguments.

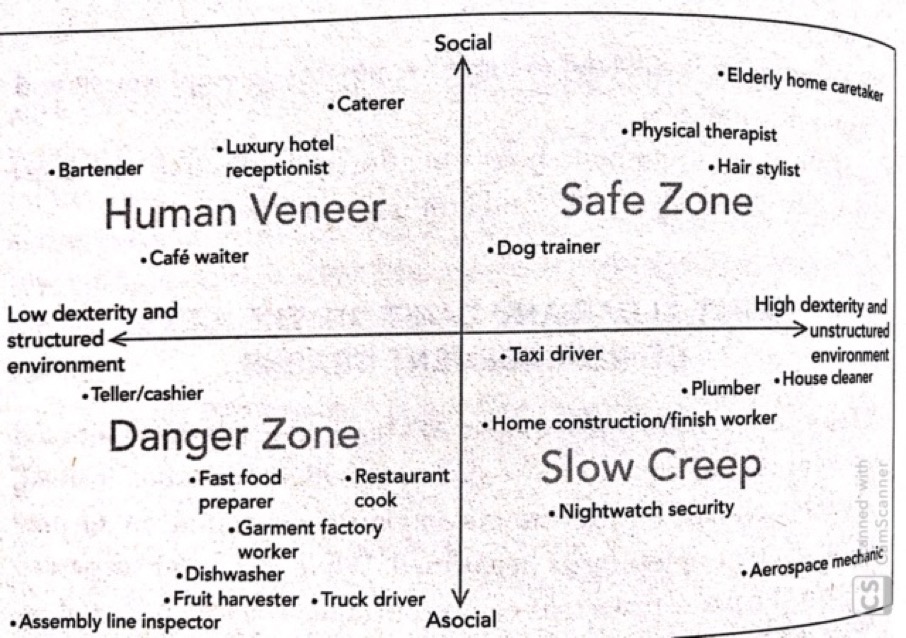

Kai-Fu Lee argues that “when it comes to job replacement, AI’s biases don’t fit the traditional one-dimensional metric of low-skill versus high-skill labour. Instead, AI creates a mixed bag of winners and losers depending on the particular content of job tasks performed. He proposed two X-Y graphs, one for physical labour and one for cognitive labour, each of which dividing the charts into four quadrants:

- the “Danger Zone”, (bottom-left),

- the “Safe Zone” (top-right),

- the “Human Veneer” (top-left), and

- the “Slow Creep” (bottom right)

These graphs give us a basic heuristic for understanding what kinds of jobs are at risk, without prejudging the impact on total employment on an economy-wide level.

Source: Kai-Fu LEE, AI Super-Powers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston New York, 2018, pages 155-156

Evaluating the impact of AI, and more generally automation, on the labour market is not an easy task. Past experience shows that new technologies take time to generate productivity and wage gains. Even though automation eventually increases the overall size of the economy, it is also likely to boost inequality in the short run, by pushing some people into lasting unemployment or lower-paid jobs. Therefore, in the short-term automation may lead to unrest and opposition, which could in turn slow the pace of automation and productivity growth, thus leaving everyone worse off in the long run.

The “glass-half-full” argument, supported for example by Paul R. Daugherty, H. James Wilson and Nicola Morini Bianzino, highlights three already-emerging job categories spurred by AI[32]: trainers (i.e. the people who are doing the data science and the machine-learning engineering), explainers (i.e. the people who explain how AI itself is working and the kind of outcomes it’s generating), and sustainers (i.e. the people who make sure that AI not only behaves properly at the outset of a new process but continues to produce the desired outcomes over time). The third category seems particularly important at the time when various experts voice big concerns over the ethical risks of AI – sustainers indeed are responsible for tackling unintended consequences of AI algorithms and how they may affect the public. It is also worth noting that regulation stimulates the second category, e.g., by some estimates, as many as 75,000 data protection officer (DPO) positions will be created in response to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) around the globe[33].

This optimistic view of AI is based on the past perspective: “As with other technology advances, writes Thomas M. Siebel, AI will soon create more jobs than it destroys. Just as the internet eliminated some jobs through automation, it gave rise to a profusion of new jobs – web designers, etc.”[34] In a report released on December 13, 2017, Gartner said “by 2020, AI will generate 2.3 million jobs, exceeding the 1.8 million that it will wipe out. In the following five years to 2025, net new jobs created in relation to AI will reach 2 million.”

On the contrary, other experts prefer to see the “glass-half-empty”. The AI-enabled computer is engaged in head-on competition with man on the labour market: it replaces man in complex functions where the human brain was deemed indispensable so far. Almost 47% of US jobs could be computerized within one or two decades[35]. It isn’t only manual labour jobs that could be affected, but also many cognitive tasks over two waves of computerization, with the first substituting computers for people in logistics, transportation, administrative and office support and the second affecting jobs depending on how well engineers crack computing problems associated with human perception, creative and social intelligence[36]. Indeed, even researchers at MIT foresee dismal prospects for many types of jobs as new technologies are increasingly adopted not only in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in professions such as law, financial services, education, and medicine. Mckinsey Global Institute reported in 2017 that by 2030 75 million to 375 million workers (3 to 14% of the global workforce) would need to switch occupational categories[37]. This is not surprising since AI has the potential to increase productivity by about 40 per cent, and is projected to contribute up to $15.7 trillion to the global economy in 2030, more than the current output of China and India combined. With the impact on productivity being competitively transformative – businesses that fail to adapt and adopt will quickly find themselves uncompetitive – all workers will need to adapt, as their occupations evolve alongside increasingly capable AI-enabled machines.